The History of the Jews in Ukraine

- Annemeet Hasidi-van Der Leij

- Jul 9, 2023

- 36 min read

Updated: May 8, 2024

April 30, 2022

The "Kyivan letter",* is perhaps the first written record of Kiev, and in Hebrew,

dated ca. 930

The history of the Jews in Ukraine goes back more than a thousand years; Jewish communities have existed in the territory of Ukraine from the time of the Kievan Rus' (late 9th to mid-13th century). Kievan Rus' was the Kievan Rus, an early medieval predecessor of present-day Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, centered on the city of Kiev. Some of the major Jewish religious and cultural movements, from Hasidism to Zionism, emerged wholly or to a large extent on the territory of modern Ukraine. According to the World Jewish Congress, Ukraine's Jewish community is the third largest in Europe and the fifth largest in the world. While it sometimes flourished, the Jewish community sometimes experienced periods of persecution and anti-Semitic discrimination in the form of pogroms and massacres.

The word pogrom means; destroy, devastate and it is used for violent attacks on certain groups; ethnic, religious or other, especially Jews, characterized above all by the destruction of their environment (homes, businesses, religious centers). Often pogroms are accompanied by physical violence against and even murder of a population group with the intention of intimidating that group and thus evicting or forcing it to assimilate with the environment.

The Russian word "pogrom" denoted an organized, time-limited, attack on the population of a town or village. When Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire, anti-Semitic attitudes were expressed in numerous blood libel cases between 1911 and 1913. In 1915, the Russian Imperial government expelled thousands of Jews from the frontier regions of the empire.

During the conflicts of the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Russian Civil War, an estimated 31,071 Jews were killed between 1918 and 1920. During the founding of the Ukrainian People's Republic

(1917-1921) pogroms continued to be perpetrated on Ukrainian territory. In Ukraine, the number of civilians killed during this period was estimated at 35,000 to 50,000.

Pogroms broke out in the northwestern province of Volhynia in January 1919 and spread to many other regions of Ukraine. Mass pogroms continued until 1921. The actions of the Soviet government in 1927, led by Stalin, led to a growing anti-Semitism in the area.

Joseph Stalin emerged as leader of the Soviet Union after a power struggle with Leon Trotsky after Lenin's death on January 21, 1924. Stalin has been accused of resorting to anti-Semitism in some of his arguments against Trotsky, who was of Jewish descent.

Trotskyists are critical of Stalinism as they oppose Joseph Stalin's theory of socialism in one country in favor of Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution. Trotskyites also criticize the bureaucracy and anti-democratic currents that developed in the Soviet Union under Stalin

Those who knew Stalin, such as Nikita Khrushchev, suggest that for a long time Stalin harbored negative feelings towards Jews who manifested themselves before the 1917 revolution. As early as 1907, Stalin wrote a letter distinguishing between a "Jewish faction" and a "true Russian faction" in Bolshevism. Stalin's secretary, Boris Bazhanov, stated that even before Lenin's death, Stalin had made gross anti-Semitic outbursts. Stalin adopted an anti-Semitic policy reinforced by his anti-Westernism. in the language of resistance to Zionism. Since 1936, during the show trial of the "Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Center" the suspects, prominent Bolshevik leaders, were accused of hiding their Jewish origins under Slavic names. Total civilian losses during World War II and the German occupation of Ukraine are estimated at seven million. More than a million Jews were shot dead by the Einsatzgruppen and their many local Ukrainian supporters in western Ukraine. In 1959, Ukraine had 840,000 Jews, a decrease of almost 70% from 1941 (within Ukraine's current borders). Ukraine's Jewish population continued to decline significantly during the Cold War. In 1989, Ukraine's Jewish population was just over half of what it was thirty years earlier (in 1959). During and after the collapse of communism in the 1990s, the majority of Jews who remained in Ukraine in 1989 left the country and moved abroad (mostly to Israel). Anti-Semitic graffiti and violence against Jews are still problems in Ukraine.

Kievan Rus'

In the 11th century, the Byzantine Jews of Constantinople had familial, cultural, and theological ties to the Jews of Kiev. For example, some 11th-century Jews from Kievan Rus took part in an anti-Karaite meeting (= Karaite Judaism is a small movement in Judaism that only accepts the written Tanakh and thus not the oral teaching from the Talmud and thus split off of Rabbinic Judaism. The word kara comes from Hebrew and means to read) which was held in Thessaloniki or Constantinople.

Galicia-Volhynia

In Halychyna (Galicia), the westernmost part of Ukraine, Jews were first mentioned in 1030. From the second part of the 14th century they were subjects of the Polish kings and magnates. The Jewish population of Halychyna and Bukovyna, part of Austria-Hungary, was extremely large; it made up 5% of the global Jewish population. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

From the foundation of the Kingdom of Poland in the 10th century to the foundation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, Poland was considered one of the most diverse countries in Europe. It became home to one of the world's largest and most vibrant Jewish communities. The Jewish community in the actual territory of Ukraine during the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth became one of the largest and most important ethnic minority groups in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian Cossacks

Bohdan Khmelnytsky: 1595 – August 6, 1657, was a Ukrainian military commander of the Zaporozhian Host, then under the rule of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

He led a revolt against the Commonwealth and its magnates (1648–1654) that resulted in the establishment of an independent Ukrainian Cossack state.

In 1654, he concluded the Treaty of Pereyaslav with the Russian Tsar and allied the Cossack Hetmanate with the Tsardom of Russia, bringing central Ukraine under Russian control. He accused Jews of assisting the Polish kingdom, as the former were often used by them as tax collectors. Bohdan tried to exterminate the Jews from Ukraine. So, according to the treaty of Zboriv, all Jewish people were forbidden to live in the territory controlled by Cossack rebels. The Khmelnytsky Uprising resulted in the deaths of an estimated 18,000-100,000 of the 40,000 to 50,000 Jews living in the area. 300 Jewish communities have been totally destroyed.

Stories of cruelty about massacre victims who had been buried alive, dismembered or forced to kill each other spread throughout Europe and beyond. Between 1648 and 1656 tens of thousands of Jews - given the lack of reliable data, it is impossible to establish more accurate figures - were killed by the rebels, and to this day the Khmelnytsky Uprising is regarded by the Jews as one of the most traumatic events in their history.

The Zaporozhian Cossacks led by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky Rise of Hasidism

The Cossack uprising left a deep and lasting impression on Jewish social and spiritual life.

In this age of mysticism and overly formal rabbinism came the teachings of Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov, (1698-1760), which had a profound effect on the Jews of Eastern Europe. His disciples taught and encouraged a new fervent form of Judaism, akin to Kabbalah, known as Hasidism. The rise of Hasidism had a major influence on the rise of Haredi Judaism, with an ongoing influence through the many Hasidic dynasties.

Russian Empire and Austrian rule

Traditional measures to keep the Russian Empire free of Jews were hampered when the main territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was annexed during the division of Poland. During the Second (1793) and Third (1795) partitions, large populations of Jews were taken over by the Russian Empire, and Catherine the Great established the "Pale of Settlement" in 1791, which included the Kingdom of Poland and Crimea. This was after several failed attempts, especially by Tsarina Elisabeth I, to expel the Jews from Russia unless they converted to Russian Orthodoxy.

The "Pale of Settlement" was a western region of the Russian Empire with several borders that existed from 1791 to 1917 in which permanent residence by Jews was permitted and then Jewish residence, permanent or temporary, was usually prohibited.

Most Jews were also still barred from residence in some towns in the Pale. A few Jews were allowed to live outside the area, including those with university degrees, the nobility, members of the wealthiest of the merchant guilds and certain craftsmen, some military personnel and some associated services, including their families, and sometimes their servants . The Archaic English term pale is derived from the Latin word palus, a post, extended to denote the area enclosed by a fence or boundary. Life in the Pale was economically bleak for many. Most people relied on small businesses or craft work that was not enough to support the population, resulting in emigration, especially in the late 1800s. Yet Jewish culture, especially in Yiddish, developed in the shtetls (small towns), and intellectual culture developed in the yeshivot (religious schools) and was also transferred abroad.

Sjtetl The Russian Empire was predominantly Orthodox Christian during the Pale's existence, unlike the Pale area with its large minorities of Jewish, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Catholic populations until the mid-19th century.

The end of the Pale's maintenance and formal demarcation coincided with the start of World War I in 1914 and finally with the fall of the Russian Empire in the February and October Revolutions of 1917. Odessa pogroms

Odessa became home to a large Jewish community in the 19th century, and in 1897 it was estimated that Jews made up some 37% of the population.

~1821 pogrom

The pogrom of 1821, perpetrated by ethnic Greeks rather than Russians, is cited in some sources as the first pogrom in modern times in Russia: in Odessa, Greeks and Jews were two rival ethnic and economic communities, living side by side.

The first pogrom in Odessa, in 1821, was related to the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, in which the Jews were accused of sympathizing with the Ottoman authorities and of aiding the Turks in killing the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory V, dragging his corpse through the streets and eventually throwing it into the Bosphorus.

~1859 pogrom

The community did not escape the horrors of this pogrom. This was in reality not a Russian but a Greek pogrom; for the leaders and almost all the participants were Greek sailors from ships in the harbor, and local Greeks who joined them. The pogrom occurred on Christian Easter.

~1871 pogrom

But after 1871, the pogroms in Odessa took on a form more typical of the rest of the Russian Empire: "Although the pogrom of 1871 was caused in part by a rumor that Jews had destroyed the church of the Greek community, many non- Greeks' participation in Russian resentment and hostility towards Jews emerged in the pogrom of 1871 when Russians joined the Greeks in attacks on Jews.

The pogrom of 1871 is seen as a turning point in Russian Jewish history: "The pogrom in Odessa led some Jewish publicists, exemplified by the writer Peretz Smolenskin, to question the belief in the possibility of Jewish integration into Christian society. attract and call for greater awareness of Jewish national identity."

~1881-1906 period

In the period after 1871, pogroms were often committed with the quiet approval of the tsarist authorities. There is evidence that during the pogrom of 1905, the army supported the crowd: the Bolshevik Piatnitsky, who was in Odessa at the time, remembers what happened: "There I saw the following scene: a gang of young men, between 20 and 25 years old. including plainclothes policemen and members of the secret police of the Russian Empire, who rounded up anyone who looked like a Jew - men, women and children - stripped them naked and brutally beat them... We immediately organized a group of revolutionaries armed with revolvers... we ran up to them and fired at them. They ran away. But suddenly a solid wall of soldiers appeared between us and the pogromists, armed to the teeth and facing us. We retreated. The soldiers left , and the pogromists came out again. This has happened a few times. It became clear to us that the pogromists were acting together with the military."

~1905 Pogrom

The 1905 Odessa Pogrom was the worst anti-Jewish pogrom in Odessa history.

Bodies of Jews killed in a pogrom of October 22, 1905 in Odessa at the cemetery Between October 18 and 22, 1905, ethnic Russians, Ukrainians and Greeks murdered more than 400 Jews and damaged or destroyed more than 1,600 Jewish properties.

Political activism and emigration

Persons of Jewish descent were overrepresented in the leadership of the Russian revolutionaries. Most of them, however, were hostile to traditional Jewish culture and Jewish political parties, loyal to the Communist Party's atheism and proletarian internationalism, and committed to eradicating any sign of "Jewish cultural particularism."

Counter-revolutionary groups, including the Black Hundreds, opposed the revolution with violent attacks on socialists and pogroms against Jews. There was also a backlash from conservative elements of society, particularly in spasmodic anti-Jewish attacks, with about five hundred being killed in one day in Odessa. Nicholas II of Russia himself claimed that 90% of the revolutionaries were Jews.

Early 20th century

In the early 20th century, anti-Jewish pogroms continued to take place in cities and towns across the Russian Empire, such as Kishinev, Kiev, Odessa, and many others.

Numerous Jewish self-defense groups (see photo above) were organized to prevent the outbreak of pogroms, the most infamous of which was led by Mishka Yaponchik in Odessa.

In 1905, a series of pogroms broke out at the same time as the revolution against the government of Nicholas II. The main organizers of the pogroms were the members of the Union of the Russian People (commonly known as the "Black Hundreds").

From 1911 to 1913, the period's anti-Semitic streak was marked by a number of blood libel cases (accusations of Jews murdering Christians for ritualistic purposes). One of the most famous was the 2-year trial of Menahem Beilis (see photo below), who was charged with the murder of a Christian boy.

The trial was shown by the authorities to illustrate the disloyalty of the Jewish population. Although Beilis was acquitted after a lengthy process by an all-Slavic jury, the legal process sparked international criticism of antisemitism in the Russian Empire.

From March to May 1915, in the face of the German army, the government expelled thousands of Jews from the border areas of the empire, which coincided with the Pale of Settlement.

The Aftermath of the First World War

During the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Russian Civil War, an estimated 70,000 to 250,000 Jewish civilians were killed in the atrocities committed in the former Russian Empire during this period. On the territory of modern Ukraine, an estimated 31,071 died in 1918-1920.

Ukrainian People's Republic

During the establishment of the Ukrainian People's Republic (1917-1921), pogroms continued to be perpetrated on Ukrainian territory.

The Pogrom Victims 1917-1921 - Age-restricted video

Between 1918 and 1921, more than 1,000 anti-Jewish riots and military actions — both of which were commonly referred to as pogroms — were documented in about 500 different locations in what is now Ukraine.

In Ukraine alone, the number of civilians killed during this period has been estimated at 35,000 to 50,000. Archives released after 1991 provide evidence of a higher number; in the period from 1918 to 1921, according to incomplete data, at least 100,000 Jews were murdered in the pogroms in Ukraine.

Yiddish was an official language in the Ukrainian People's Republic, while all government posts and institutions had Jewish members. A Ministry of Jewish Affairs was established (it was the first modern state to do so). All rights of Jewish culture were guaranteed. All Jewish parties abstained or voted against the Fourth Universal of the Tsentralna Rada (=Central Council or Central Soviet) of January 25, 1918, which aimed to sever ties with Bolshevik Russia and declare a sovereign Ukrainian state, as all Jewish parties were strongly against Ukrainian independence.

The Ukrainian People's Republic did issue orders condemning pogroms and tried to investigate them. But it lacked the authority to stop the violence. In the last months of its existence, it lacked power to create social stability.

Between April and December 1918, the Ukrainian People's Republic did not exist and was overthrown by the Ukrainian state of Pavlo Skoropadsky, which ended the experiment in Jewish autonomy.

Provisional Government of Russia and Soviets

The revolution of February 1917 brought a liberal Provisional Government to power in the Russian Empire. On March 21/April 3, the government abolished all "discrimination based on ethnic, religious or social grounds". The Pale was officially abolished. The lifting of restrictions on the geographical mobility and educational opportunities of Jews led to a migration to the major cities of the country.

A week after the Bolshevik revolution of October 25 / November 7, 1917, the new government proclaimed the "Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples [Nations] of Russia", promising all nationalities the right to equality, self-determination and secession. Jews were not specifically mentioned in the statement, reflecting Lenin's view that Jews did not constitute a nation.

In 1918, the RSFSR Council of Ministers issued a decree entitled "On the Separation of Church and State and School of Church", granting religious communities the status of legal entities, the right to property and the right to enter into contracts. taken away. The decree nationalized the property of religious communities and banned their assessment of religious education. As a result, religion could only be taught or studied privately. On February 1, 1918, the Commissariat for Jewish National Affairs was established as a subsection of the Commissariat for Nationality Affairs. It was tasked with establishing the "dictatorship of the proletariat in the Jewish streets" and drawing the Jewish masses to the regime, while advising local and central institutions on Jewish issues. The commissariat was also expected to fight the influence of Zionist and Jewish Socialist parties.

On July 27, 1918, the Council of People's Commissars issued a decree stating that antisemitism is "deadly to the cause of the ... revolution". Pogroms were officially banned. On October 20, 1918, the Jewish Section of the CPSU (Yevsektsia= the Jewish Section of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) was established for the Jewish members of the party; its aims were similar to those of the Jewish Commissariat.

Pogroms in western Ukraine

The pogroms that broke out in the northwestern province of Volhynia in January 1919 spread to the towns and villages of many other regions of Ukraine in February and March. After Sarny it was Ovruch's turn, northwest of Kiev. In Tetiev, about 4,000 Jews were murdered on March 25, half of them in a synagogue set on fire by Cossack troops led by Colonels Kurovsky, Cherkowsy and Shliatoshenko. In Dubovo (June 17), 800 Jews were beheaded continuously. According to David A. Chapin, the town of Proskurov (now Khmelnitsky), near the town of Sudilkov, was "the site of the worst atrocities committed against the Jews this century before the Nazis."

Pogroms in Podolia

The Proskuriv pogrom took place on February 15, 1919 in the city of Proskurov during the Ukrainian Independence Day.

war, which was initiated by Otaman Ivan Semesenko (1894-1920).

The massacre was carried out by soldiers of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) of Ivan Samosenko. They were instructed to save the ammunition in the process, using only lances and bayonets.

In just three and a half hours, at least 1,500 Jews were murdered, up to 1,700 by other estimates, and more than 1,000 were injured, including women, children and the elderly.

A witness writing about the violence said: "It is impossible to imagine what happened here on Saturday, February 15, 1919. This was not a pogrom. It was like the Armenian massacre."

According to historians Yonah Alexander and Kenneth Myers, the soldiers marched into the center of the city, accompanied by a military mob and under the motto "Kill the Jews and save the Ukraine."

The massacre was arguably the bloodiest of the Russian Civil War, and it was part of a much larger wave of anti-Semitic violence in Ukraine between 1917 and 1921: soldiers serving the Ukrainian People's Republic, the "white" Russian volunteer army, independent warlords, bandits and, to a lesser extent, the Red Army has murdered, raped, assaulted, mutilated and dispossessed tens of thousands of Jews.

The army of the Ukrainian People's Republic (photo above)was arguably the worst offender. The UPR had declared independence from Russia in January 1918 and became the focus of many nationally conscious Ukrainians' desire for liberation.

However, according to the most reliable statistical research, his troops were responsible for about two-fifths of all pogroms and half of all deaths.

A few days later, the Red Cross representative in Proskuriv witnessed Semosenko's oral report to Symon Petliura. He was a Ukrainian publicist, writer, journalist, politician and statesman. During the Russian Civil War, from 1918 to 1920, he headed the independent Ukrainian Republic (UPR).

Symon Petliura (photo above) was of Cossack origin. Unfortunately, UPR head Symon Petliura Otaman did not punish Ivan Semesenko for the mass murder of Jews. Semesenko was shot in the early 1920s for not following Petliura's orders.

A local Ukrainian public figure, Trokhym Fedorovych Verkhola (1883-1922), a Ukrainian social democrat, teacher, artist and educator, rebelled against this mass murder of civilians.

After the revolution of 1917, he was elected as a deputy to the municipal council, the head of the Prosvita Association [Enlightenment] and as a representative in the Constituent Assembly of Russia. Verkhola took part in the origin of the Ukrainian national revival in Proskuriv. For a time he was even the mayor of the city.

Verkhola had good relations with the local Jewish community for many years. There was a charming episode in March 1917 when he was preparing the first Ukrainian public demonstration in Proskuriv after the overthrow of tsarism. Preparation for the demonstration was on a Saturday and all the city's shops were closed for Shabbat, but Verkhola agreed with the local Jews to receive yellow and blue fabric for sewing Ukrainian flags. During the reign of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky, he was arrested by the Austro-Hungarian military authorities and sent to the court in Lviv. After the overthrow of hetman (=Hetman of Ukraine is a former historical government office and a political institution of Ukraine equivalent to a head of state or a monarch) and the coming to power of Symon Petliura, Verkhola returned to Proskuriv on February 12, 1919 , three days before the pogrom.

Jews in Proskurov (Khmelnitskiy), Ukraine, standing beside a mass grave

When Verkhola heard about the massacre of Jews, he went into the streets of the city and saw the slaughtered victims near many buildings. Verkhola urgently began collecting medicines for the injured from pharmacies across the city.

The next morning, on February 16, Verkhola called an emergency meeting of the city council, attended by Otaman Semesenko and his aide, the military commander Kiverchuk. Just outside the city hall building, he saw Cossacks murdering a Jew. Verkhola demanded an immediate end to the Proskuriv massacre and ordered Semesenko's soldiers to return from the neighboring town of Felshtin, where they were sent out for another mass murder of Jews.

Verkhola declared right in front of the assassins commander: “What are you doing, Otaman?! You are not a Ukrainian or Ukrainian Cossack!” Verkhola demanded an end to the pogrom "for the sake of Ukraine's honor".

Semesenko denied the fact of the massacre. He said: "I have ordered the extermination of the Bolsheviks, and if there are any old men, women and children among the Jews who are Bolsheviks, it is their fault, not mine."

Otaman Semesenko arrested Verkhola and wanted to shoot him, but the Ukrainian deputy was released at the request of local Ukrainian politicians.

It is interesting to note that the pogrom in Proskuriv was halted after the city's Ukrainian activists sent an urgent telegram to Yevhen Konovalets, the commander of the Ukrainian army (pictured below).

The future creator of the OUN [Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists] immediately ordered Otaman Semesenko to stop the massacre.

Trokhym Verkhola remained a Ukrainian public figure in Proskuriv in 1919-1920. The Jews have always remembered with gratitude that Verkhola helped the victims of the pogrom and defended the Jews.

Fleeing from the Bolsheviks, Verkhola fled to Lviv in 1921. Local Jews helped him financially, but Trokhym was already seriously ill with tuberculosis. He died in Lviv in 1922 at the age of 39.

Verkhola is remembered in the memoirs of Ukrainian activist Natalia Doroshenko-Savchenko (1888-1974).

From 1913-17 she lived in Proskuriv and together with Trohym Verkhola took an active part in Ukrainian national life. In 1921 she moved to Lviv, where she was a librarian at the Prosvita Society before 1939. Later she emigrated with her family to the United States. Her memoirs were published in Svoboda [Freedom] (New York, December 25, 1955) and were titled "The Beginning of the National Revolution in Proskurivshchyna."

"T. Verkhola became the soul of the Community. He was a man of inexhaustible energy, extremely mobile, and above all completely devoted to the cause at hand. He was also an excellent artist - a painter. In addition, he enjoyed popularity among the peasants from Proskurivshchyna, because he himself came from the peasants of Satanov. He was highly regarded by the Jewish community. Incidentally, when later, in 1919, a Jewish pogrom broke out in Proskuriv, Verkhola did much to calm the situation. Grateful Jews helped him when he emigrated to Lviv, when he was already seriously ill."

The name Trokhym Verkhola is inscribed on a Jewish memorial on a mass grave, for the victims of the pogrom in Proskurov, now Khmelnitskiy, Ukraine. (picture below)

Kievan Rabbi Moshe Reuven Azman, one of the Chief Rabbis of Ukraine at present, held a memorial prayer at this monument.

The town of Proskuriv was renamed Khmelnytskyi in 1954 during the Stalinist era, despite the fact that Bohdan Khmelnytsky himself carried out a terrible pogrom against the Jews there as early as the 17th century.

The series of Jewish pogroms in various places in Ukraine culminated in the Kiev pogroms of 1919 between June and October of that year.

On October 14, 2017, the recently established Day of the Defender of Ukraine, the municipal council of the city of Vinnytsia, in west-central Ukraine, erected a statue to Symon Petliura. This caused consternation among many Jews in Ukraine and abroad, not least because the statue was in Ierusalymka, the historic Jewish quarter of Vinnytsia. But it also provided the Kremlin with further ammunition to discredit Ukraine as a stronghold of fascism and anti-Semitism. “Petliura was a man of Nazi views,” said Vladimir Putin at the time, “an anti-Semite who slaughtered Jews in times of war.”

The Kiev Pogroms

In 1919, there were a series of anti-Jewish pogroms in various places around Kiev, carried out by troops of the White Volunteer Army. The White Volunteer Army was a counter-revolutionary army in southern Russia during the Russian Civil War. The army existed from 1918 to 1920.

The military was part of the alliance known as the White Army.

-Zhytomyr, January 7-10, 1919: 15 Jewish youths were killed when they came to defend the local Jewish population, and Christian student Nicholas Blinov, who also tried to defend them, also lost his life. Ten young Jews from nearby Chudnov were also killed while on their way to help the Jews of Zhytomyr.

-Zhytomyr, March 22-25, 1919: According to witnesses, 317 were killed. Local Christian neighbors have hidden a number of Jews in their homes.

-Zhytomyr, May 7-8, 1919: The part of the city known as "Podol" was destroyed and 20 Jews were killed.

-Skvyra, June 23, 1919: A pogrom in which 45 Jews were massacred, many were seriously injured and 35 Jewish women were raped by insurgents from the army.

-Justingrad, August 1919: Here a pogrom made its way through the shtetl with an unspecified number of murdered Jewish men and raped Jewish women.

-Ivankiv District, October 18-20, 1919: In the pogrom carried out by troops of the Cossack and Volunteer Army, 14 Jews were massacred, 9 injured and 15 Jewish women and girls raped by units in three days of massacre.

The Cossack and Volunteer Army

Bolsheviks/USSR Power Consolidation

In July 1919 the Central Jewish Commissariat dissolved the kehillot (Jewish Municipal Councils). The kehillot had provided a number of social services to the Jewish community.

In 1921, many Jews in the newly formed USSR emigrated to Poland, as a peace treaty in Riga gave them the right to choose the country they preferred. Several hundred thousand joined the already numerous Jewish minority of the Second Polish Republic.

On January 31, 1924, the Commissariat for Nationalities Affairs was dissolved. On August 29, 1924, an official body for Jewish resettlement, the Commission for the Settlement of Jewish Workers on the Land (KOMZET) was established. KOMZET studied, managed and financed Jewish resettlement projects in rural areas. A public organization, the Association for the Agricultural Organization of Working-Class Jews in the USSR (OZET), was established in January 1925 to help recruit settlers and support KOMZET's colonization work.

In the early years, the government encouraged Jewish settle-ments, especially in Ukraine. Support for the project waned over the next decade. OZET was dissolved in 1938, after years of declining activity. The Soviets established three Jewish natio-nal raions (=often translated as district) in Ukraine and two in Crimea - national raions occupying the 3rd level of the Soviet system, but all were disbanded at the end of World War II.

The cities with the largest populations of Jews in 1926 were Odessa, 154,000 or 36.5% of the total population; Kyiv, 140,500 or 27.3%; Kharkiv, 81,500 or 19.5%; and Dnipropetrovsk, 62,000 or 26.7%. In 1931 the Jewish population of Lviv was 98,000 or 31.9%, and in Chernivtsi 42,600 or 37.9%. On April 8, 1929, the new Religious Societies Act codified all previous religious legislation. All meetings of religious associations had to be pre-approved; lists of members of religious associations had to be provided to the authorities.

In 1930 the Yevsektsia was dissolved and there was now no central Soviet Jewish organization. While the body had served to undermine Jewish religious life, its dissolution also led to the disintegration of Jewish secular life; Jewish cultural and educational organizations gradually disappeared.

When the Soviet government reintroduced the use of internal passports in 1933, "Jewish" was considered an ethnicity for these purposes.

The Soviet famine of 1932-1933 hit the Jewish population in Ukraine very hard (see photo below) and led to a migration from the shtetls to the overcrowded cities.

When the Soviet government annexed territory from Poland, Romania (both were to be incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR after World War II) and the Baltic states, about two million Jews became Soviet citizens.

Restrictions on Jews that had existed in the previously independent countries were now lifted. At the same time, Jewish organizations in the newly acquired territories were closed down and their leaders were arrested and exiled. About 250,000 Jews escaped or were evacuated from the annexed areas to the Soviet interior prior to the Nazi invasion.

Jewish settlement in Crimea

In 1921, Crimea became an autonomous republic. In 1923, the Central Committee of the All-Union passed a motion to resettle a large part of the Jewish population of Ukrainian and Belarusian cities, 570,400 families, to Crimea.

Jewish farmers of a Crimean collective celebrate the laying of the foundation stone for a new school in 1927

The plan to further resettle Jewish families was reaffirmed by the Central Committee of the USSR on July 15, 1926, allocating 124 million rubles to the task, and also receiving 67 million from foreign sources.

The Soviet initiative of Jewish settlement in Crimea was opposed by Symon Petliura, who considered it a provocation. This line of thought was supported by Arnold Margolin. He was a Ukrainian diplomat, lawyer, active participant in the Ukrainian and Jewish community and political affairs; a lawyer who became world famous as counsel for Menahem Beilis in the infamous trial of Jewish blood libel in Kiev from 1911 to 1913. He was a judge of the Supreme Court of Ukraine, Secretary of State for Ukraine and a member of the Ukrainian delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference between 1918 and 1919. He argued that establishing Jewish colonies there would be dangerous.

The Soviets twice tried to establish Jewish autonomy in Crimea; once, in the 1920s, with the support of the American-Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and secondly, in 1944, by the Jewish Antifascist Committee.

WWII

Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated at seven million, including nearly 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews, nearly 80 percent of whom were shot dead by the Einsatzgruppen and by local Ukrainian supporters in various regions of Ukraine.

Babi Yar:

During the first week of the German occupation of Kiev, there were two major explosions. These explosions devastated the German headquarters and areas around the main street of the city center (Khreshchatyk Street). The explosions killed a large number of German soldiers and officials. Although the explosions were caused by mines left by retreating Soviet soldiers and officials, the Germans used the sabotage as a pretext to kill the Jews still in Kiev.

Possibly the largest two-day massacre of the Holocaust. Syret's concentration camp was also located in the area. Massacres took place in Babi Yar from September 29, 1941 to November 6, 1943, when Soviet troops occupied Kiev.

Babi Yar or Babyn Yar is a ravine in the Ukrainian capital Kiev and a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany's troops during their campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. The first and best-documented massacre took place on September 29-30, 1941, in which 33,771 Jews were murdered.

Portrait of five-year-old Mania Halef, a Jewish child, who was later murdered during the mass execution in Babi Yar.

Other Jewish victims of the Babi Yar massacre

The victims were called to the site, forced to undress and then forced into the ravine. Sonderkommando 4a, a special detachment of Einsatzgruppe C under SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel, shot them down in small groups.

It was a trap – and many knew it. The Ukrainian engineer Fedir Phido spoke of the sorrow of the Jews on the way to Babi Yar, as quoted by the Dutch historian Karel Berkhoff in his book 'Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule': “Many thousands of people, mainly old – but also middle-aged people were not missing – headed for Babi Yar. And the children - my God, there were so many children! All this was moving, laden with luggage and children. Here and there old and sick people who did not have the strength to move on their own were carried on carts unaided, probably by sons or daughters. Some cry, others comfort. Most moved in a selfish way, in silence and with a doomed look. It was a terrible sight."

They were all taken to Babi Yar, which means "grandmother's ravine" or "an old woman's ravine" in Ukrainian. The Soviet NKVD had already used this site to carry out massacres – it provided a remote firing range near Kiev's large population center.

”There was a whole process that started where the people were supposed to gather," said Boris Czerny, a professor of Russian literature and culture at the University of Caen and a specialist in the history of the Jews of Eastern Europe. “People were asked to bring their most precious possessions, then they had to give away their ID at one place, then at another time they had to give away the belongings they brought, and finally there was a place where they had to undress.”

“Once undressed, the Jews were led into the ravine which was about 150 meters long by 30 meters wide and at least 15 meters deep... When they reached the bottom of the ravine, they were grabbed by members of the Schultpolizei and had to lie down on the Jews who had already been shot.

That all happened very quickly. The corpses were literally in layers. A police gunner came by and shot each Jew in the neck with a submachine gun… I saw this sniper standing on layers of corpses and shooting one after another… The sniper walked over the bodies of the executed Jews to the next Jew, meanwhile, lay down and shot him. On that day I may have shot about 150 to 250 Jews. The entire shooting went smoothly. The Jews surrendered to their fate like sheep for the slaughter,” reads the description of the slaughter by SS officer named Viktor Trill (see photo below). “I saw a huge hole that looked like a dried-up river bed. Inside were layers of bodies. The Jews had to lie on the bodies and were shot in the neck.”

Historian Abram Sachar describes the extermination at Babi Yar: “The riddled bodies were covered with a thin layer of earth and the following groups had to lie over them to be killed in the same way. Carrying out the murder of 33,771 people in the space of two days could not guarantee that all the victims had died. There were a few who survived and, although badly injured, managed to crawl out from under the corpses and seek shelter."

"After the burial, the earth 'moved' from the helpless final battle for the lives of the wounded but buried alive in this mass grave. A week later, blood was still seeping from this macabre place."

The elderly Olha Havrylivna – aged 12 when she witnessed the horrifying atrocity here – recalled: “We saw arrests, murders, executions. They brought them to the edge of a pit and shot them. But you could see the well moving, for some were still alive.”

August Häffner, left, and Viktor Trill, two of the perpetrators of the Babi Yar massacre

It was members of Einsatzgruppen C, along with two groups of the German Order Police and troops of the collaborationist Ukrainian Auxiliary Police who shot and killed 33,771 people throughout the day - and the next day.

This wasn't the first episode in what historians call the "Holocaust by Bullets": A month earlier, 23,600 Jews suffered the same fate in Kamenets-Podolski, a Ukrainian town near the Hungarian border.

However, the scale of the massacre at Babi Yar - and its systematic nature - made it a turning point in the Holocaust.

It was the first time in history that a premeditated massacre virtually wiped out the entire Jewish population of a major European city.

Between 1941 and 1944, nearly 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews were murdered. Nearly 80 percent of them were shot.

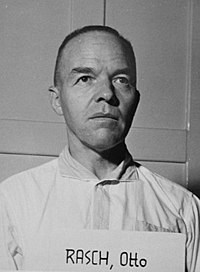

The decision to kill all Jews in Kiev was taken by the military governor Major General Kurt Eberhard, the police commander of Army Group South, SS-Obergruppen fuhrer Friedrich Jeckeln and the commander of the Einsatz-gruppe C Otto Rasch.

Friedrich Jeckeln and Otto Rash Sonderkommando 4a, as a sub-unit of Einsatzgruppe C, together with the assistance of the SD and Order Police battalions with the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, supported by the Wehrmacht, carried out the orders.

Sonderkommando 4a and the 45th battalion of the Teutonic Order Police carried out the shelling. Soldiers of the 303rd Battalion of the Teutonic Order Police were guarding the outer perimeter of the execution site at the time.

The massacre was the largest mass murder under the auspices of the Nazi regime and its Ukrainian associates during the campaign against the Soviet Union, and it has been called "the largest single massacre in the history of the Holocaust" to date.

The ravine at Babi Yar was a killing site for two years after the September 1941 massacre. There, Germans stationed in Kiev murdered tens of thousands of people, both Jews and non-Jews. Other groups of people killed at Babi Yar included: patients from a local psychiatric hospital, Roma (Gypsies), Soviet POWs and civilians.

The killings at Babi Yar ravine continued until the fall of 1943, just days before the Soviets recaptured Kiev on November 6.

It is estimated that some 100,000 people, Jews and non-Jews, have been murdered in Babi Yar.

As the Red Army approached in August 1943, the Germans began a cover-up to hide what had happened at Babyn Yar. To do this, they used prisoners held in the Syrets concentration camp which is close to the Babi Yar ravine.

The Syrets camp was established by the Germans in May 1942. It served for the internment of Soviet POWs, partisans and Jews who had survived the massive actions of late September 1941.

To cover up the mass shootings at Babi Yar, the Germans ordered 321 inmates from Syrets to excavate the mass graves and burn the remains of victims. Eighteen prisoners who had gone into hiding testified against the Soviet authorities about these crimes in November 1943.

In January 1946, 15 members of the German police in Kiev were tried for the crimes committed in Babi Yar. Dina Pronicheva, a Jewish survivor of the September massacre, testified before a Soviet court.

In one of her post-war testimonies, Pronicheva described what she saw in Babi Yar:

"Each time I saw a new group of men and women, the elderly and children who were forced to take off their clothes. All [of them] were taken to an open pit where machine guns shot them. Then another group was brought…. With with my own eyes I have seen this horror. Although I was not close to the well, terrible cries of panicked people and quiet children's voices who cried "Mother, mother..." reached me."

In 1947, Paul Blobel was tried before the American military tribunal in Nuremberg. He was the commander of Sonderkommando 4a, the Einsatzgruppe unit responsible for the massacre of Jews at Babi Yar in September 1941.

Blobel was one of 24 defendants in the Einsatzgruppen trial and pleaded not guilty. His defense argued that he had simply followed orders. Nevertheless, Blobel was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was hanged in Landsberg Prison on June 8, 1951.

In 1959, Erich Koch, who had served as Reichskommissar in Ukraine, was tried and sentenced to death by a Polish court for crimes committed in occupied Poland during World War II.

He was never tried or convicted for his war crimes in occupied Ukraine. Due to ill health, Koch's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He died of natural causes in his prison cell at Barczewo Prison in Poland on November 12, 1986.

A few years after the Nazis attempted to cover their own tracks, the Soviets attempted to flood the ravine with mud. Then in the 1960s there was anger about plans to build a sports stadium there. The construction of a TV tower right next to the memorial in the 1970s was another attempt to "destroy the memory of the Holocaust".

Despite many efforts, there was no memorial at the site until the Soviets installed a memorial in 1976.

The Jewish tragedy in Babi Yar was less emphasized and the text on the monument referred to thousands of civilian casualties without indicating that the vast majority of them were Jewish.

As the Soviet Union disintegrated in the wake of Ukraine's declaration of independence in August 1991, a menorah-shaped monument was erected to the Jewish victims of Babi Yar on September 29, the 50th anniversary of the mass shooting.

The Babi Yar massacre is surpassed only by the Odessa massacre where more than 50,000 Jews were killed later in 1941 in October 1941 (committed by German and Romanian troops), and by Aktion Erntefest of November 1943 in occupied Poland with 43,000 casualties . Operation Harvest Festival (German: Aktion Erntefest) was the murder of up to 43,000 Jews at the Majdanek, Poniatowa and Trawniki concentration camps by the SS, the Order Police battalions, and the Ukranian Sonderdienst on 3–4 November 1943.

Victims of other massacres at the site included Soviet POWs, communists, Ukrainian nationalists and Roma. It is estimated that between 100,000 and 150,000 people were killed in Babi Yar during the German occupation.

The Lviv/Lwów Pogroms

It was the successive pogroms and massacres of Jews in June and July 1941 in the city of Lwów in Eastern Poland/Western Ukraine (now Lviv, Ukraine). The Soviet Union occupied Lwów in September 1939, according to secret provisions of the German-Soviet Pact. Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, occupying Lvov within a week. The Germans claimed that the city's Jewish population had supported the Soviets. Ukrainian mobs went on a rampage against Jews. They stripped and beat Jewish women and men in the streets of Lvov. Ukrainian partisans supported by German authorities killed about 4,000 Jews in Lvov during this pogrom. US forces discovered this 8mm footage in SS barracks in Augsberg, Germany, after the war.

A woman stripped down to her underwear is chased by both a uniformed boy with a cane and an adolescent. The action takes place near Zamarstyniv Street Prison [Lviv].

One of the characteristic features of the pogrom was the abuse and humiliation of Jewish women. The scenes in Zamarstyniv Street were photographed by a German camera crew.

The massacres were perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists, German death squads (Einsatzgruppen) and local populations from June 30 to July 2 and from July 25 to 29, during the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Thousands of Jews were killed in both the pogroms and the Einsatzgruppen murders.

Ukrainian nationalists targeted Jews in the first pogrom under the pretext of their alleged responsibility for the massacre of prisoners of the NKVD (= the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Soviet Union) in Lviv, leaving thousands of corpses in three Lviv prisons .

The subsequent massacres were directed by the Germans in the context of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe.

The pogroms were ignored or obscured in Ukrainian historical memory, starting with the Ukrainian nationalist's actions to clear or whitewash his own record of anti-Jewish violence.

The Odessa massacre

his was the massacre of the Jewish population of Odessa and surrounding towns in the Transnistria Governorate in the fall of 1941 and the winter of 1942, while under Romanian control. Depending on the accepted terms of reference and scope, the Odessa massacre refers either to the events of October 22-24, 1941, in which some 25,000 to 34,000 Jews were shot or burned, or to the murder of more than 100,000 Ukrainian Jews in the city. and the areas between the Dniester and Bug rivers, during the Romanian and German occupation that took place after the massacre.

As of 2018, it was estimated that up to 30,000 people, mostly Ukrainian Jews, were murdered in the actual massacre, which took place from October 22 to 23, 1941. The main perpetrators were Romanian soldiers, Einsatzgruppe SS and local ethnic Germans.

Post-war situation

Ukraine had 840,000 Jews in 1959, a decrease of almost 70% from 1941 (within Ukraine's current borders). Ukraine's Jewish population declined significantly during the Cold War. In 1989, Ukraine's Jewish population was just over half of what it was thirty years earlier (in 1959).

The vast majority of Jews remaining in Ukraine in 1989 left Ukraine and moved to other countries (mostly to Israel) in the 1990s during and after the collapse of communism.

Independent Ukraine

In 1989, a Soviet census counted 487,000 Jews living in Ukraine. Although state discrimination ended almost quickly after Ukrainian independence in 1991, Jews were still discriminated against in Ukraine in the 1990s. For example, Jews were not allowed to visit certain educational institutions. Anti-Semitism has since declined.

According to the European Jewish Congress, as of 2014, there are 360,000-400,000 Jews in Ukraine.

In the 1990s, some 266,300 Ukrainian Jews immigrated to Israel as part of a wave of mass emigration of Jews from the former Soviet Union to Israel in the 1990s. The 2001 Ukrainian census counted 106,600 Jews living in Ukraine (the number of Jews also decreased due to a negative birth rate).

According to Israel's Minister of Public Diplomacy and Diaspora Affairs, at the beginning of 2012, there were 250,000 Jews in Ukraine, half of them in Kiev.

In November 2007, an estimated 700 Torah scrolls previously seized from Jewish communities during the communist rule of the Soviet Union were returned by state authorities to Jewish congregations in Ukraine. The Ukrainian Jewish Committee was established in Kiev in 2008 with the aim of focusing the efforts of Jewish leaders in Ukraine on solving the community's strategic problems and addressing socially important issues.

The Committee stated its intention to become one of the world's most influential organizations to protect the rights of Jews and "the most important and powerful structure for the protection of human rights in Ukraine".

In the 2012 Ukrainian parliamentary elections, the All-Ukrainian Union "Svoboda"** and political opponents won its first seats in the Ukrainian parliament, with 10.44% of the vote and the fourth most seats of the national political parties; This raised concerns among Jewish organizations, both inside and outside Ukraine, who accused "Svoboda" of overt Nazi sympathies and being anti-Semitic.

Below is a video about the BBC's Svoboda party:

In May 2013, the World Jewish Congress labeled the party a neo-Nazi. "Svoboda" has denied being anti-Semitic.

Anti-Semitic graffiti and violence against Jews are still a problem in Ukraine.

The Revolution of Dignity, also known as the Maidan Revolution, took place following the Euromaidan protests, in February 2014, when deadly clashes between protesters and domestic troops in the Ukrainian capital Kiev resulted in the ousting of President-elect Viktor Yanukovych and the overthrow of the Ukrainian government.

In November 2013, a wave of large-scale protests erupted in response to President Yanukovych's sudden decision to reconsider the association agreement between the European Union and Ukraine, while in February of that year the Ukrainian parliament overwhelmingly voted in favor of an agreement with the European Union. Instead, Yanukovych leaned towards closer ties with Russia, which pressured Ukraine to refuse the EU deal, and join the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

The pro-Western protests lasted for months and widened in scope, with calls for the resignation of Yanukovych and the government of Mykola Azarov. The repressive anti-protest laws passed by parliament fueled even more anger.

The initially peaceful demonstrations became increasingly violent and on January 22, four people were killed in violent clashes between demonstrators and the police. Protesters occupy government buildings across the country.

A large, barricaded protest camp occupied Independence Square in central Kiev.

In mid-February, an amnesty agreement was signed with the protesters that would spare them and those previously detained criminal charges in exchange for leaving occupied buildings.

The demonstrators evacuated all occupied buildings belonging to the regional state administration on February 16.

Since the end of the Euromaidan protests in February 2014, unrest has gripped southern and eastern Ukraine and escalated in April 2014 to the ongoing war in Donbas.

Donbas is a historical, cultural and economic region in south-eastern Ukraine. Parts of the Donbas are under the control of separatist groups as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian war.

In April 2014, leaflets were distributed by three masked men as people left a synagogue in Donetsk (the largest city in Donbas). The leaflet called on Jews to register to avoid losing their property and citizenship, quote: "as the leaders of the Jewish community of Ukraine support the Banderite*** and are hostile to the Donetsk Orthodox Republic and its citizens standing." While many speak of a hoax (concerning the authorship of the tracts) that took on international proportions, the fact that these flyers were distributed remains undisputed.

As a result of growing Ukrainian unrest in 2014, Ukrainian Jews who made aliyah from Ukraine in the first four months of 2014 reached 142% more than in the previous year. 800 people arrived in Israel between January and April and more than 200 registered for May 2014.

On the other hand, Chief Rabbi and Chabad Envoy of Kiev, Rabbi Jonathan Markovitch, claimed in late April 2014: “Today you can come to Kiev, Dnipro or Odessa and walk through the streets openly dressed as a Jew, with nothing to be afraid of ".

In August 2014, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported that the International Association of Christians and Jews is organizing charter flights to immigrate at least 150 Ukrainian Jews to Israel in September.

Jewish organizations in Ukraine, as well as the US Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish Agency for Israel and the Dnipropetrovsk Jewish Community, have arranged temporary homes and shelters for hundreds of Jews fleeing war in Donbas in eastern Ukraine. Hundreds of Jews have reportedly fled the cities of Luhansk and Donetsk, and Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein stated (in August 2014) that more Jews could leave for Israel if the situation in eastern Ukraine continues to deteriorate.

In 2014, Jews Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Volodymyr Groysman were appointed governor of Ukraine's Dnipropetrovsk region and speaker of parliament, respectively. Groysman became Prime Minister of Ukraine in April 2016. Ukraine elected its first Jewish president in the 2019 presidential election, where former comedian and actor of the TV series Servant of the People, Volodymyr Zelensky, defeated incumbent Petro Poroshenko.

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

In February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, the Israeli embassy remained open on Shabbat to prepare for the evacuation of an estimated 200,000 people.

In all, only 97 Jews chose to flee Ukraine for Israel!

In addition, 140 Jewish orphans have fled from Ukraine to Romania and Moldova. 100 Jews fled from Ukraine to Belarus and eventually to Israel.

On March 2, 2022, the Jewish Agency for Israel reported that hundreds of Ukrainian Jewish war refugees sheltering in Poland, Romania and Moldova would leave for Israel the following week.

On March 13, 2022, 600 Jews who fled Ukraine went to Israel, and on March 21, 2022, that number was 12,000.

As of April 7, 2022, the number of Jews from Ukraine who have gone to Israel is reported to be 10,000.

Jewish communities

As of 2012, Ukraine had the fifth largest Jewish community in Europe and the twelfth largest Jewish community in the world, after South Africa and ahead of Mexico.

The majority of Ukrainian Jews live in four major cities: Kiev (about half of all Jews living in Ukraine), Dnipro, Kharkiv and Odessa. Opened in October 2012 in Dnipro, the multi-purpose Menorah Center is probably one of the largest Jewish community centers in the world.

There is a growing trend among some Israelis to visit Ukraine on a "roots trip" to follow in the footsteps of Jewish life there. Among the sights, Kiev is usually mentioned, where it is possible to follow the paths of Sholem Aleichem and Golda Meir; Zhytomyr and Korostyshiv, where one can follow in the footsteps of Haim Nahman Bialik; Berdychiv, where one can follow the life of Mendele Mocher Sforim; Rivne, where one can follow the course of Amos Oz; Buchach – the path of S.Y. Agnon; Drohobych - the place of Maurycy Gottlieb and Bruno Schulz.

Haïm Nahman Bialik, eyewitness to the waves of violence in Odessa in May 1881, exclaims his horror and disgust:

"Get up, go to the city of the massacre, come to the courtyards

Look with your eyes and feel the barriers with your hands

And the trees, the stones and the plaster of the walls

The clotted blood and hardened brains of the victims (...)

Tomorrow the rain will fall, will carry it in a ditch, towards the fields

The blood will no longer scream from the wells or the haumiers,

for it will perish in the abyss or water the thistle

And everything will be as before, as if nothing had happened."

- Extract from the poem be'ir haharegah (in fr. In the city of the massacre)

*The "Kyivan Letter": We know that Kiev had a Jewish quarter called Zhidove. The Kyivan letter, is a letter from the early 10th century (c.930) believed to have been written by representatives of the Jewish community in Kiev. The letter, a recommendation in Hebrew written on behalf of a member of their community, was part of a huge Cairo Geniza collection brought to Cambridge in 1962. A geniza is a temporary repository for worn or damaged sacred books and manuscripts in the Hebrew language prior to burial. The letter is dated by most scholars to around 930 CE. We also know that Kiev princes generally welcomed the participation of Jews in trade and finance, and that from the late eleventh century Kyivan Rus' was a refuge for Western European Jews fleeing Crusader persecution. However, in 1113 a mob looted the Jews in the Zhidove district of Kiev, as well as the highest members of the aristocracy. **Svoboda, "Al-Ukrainian Union "Freedom", also called "Freedom Party" is a Right to extreme right-wing nationalist Ukrainian political party, also characterized by some as fascist or neo-Nazi. The 2012 parliamentary elections led to Svoboda entered the Ukrainian parliament as the country's fourth party with 37 seats.

During the 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary elections, the party still had 6 seats in parliament.

***The Banderites are members of an assortment of right-wing organizations in Ukraine. The term is derived from the name of Stepan Bandera (1909-1959), head of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists that was formed in 1929 as an amalgamation of movements including the Union of Ukrainian Fascists. The union, known as OUN-B, had been involved in several atrocities, including murder of civilians, most of whom were ethnic Poles. This was a result of the organization's extreme Polonophobia, but the victims also included other minorities, such as Jews and Roma. The term "Banderites" was used by the Bandera adherents themselves, by others during the Holocaust and during the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia by OUN-UPA of 1943-1944.

These massacres resulted in the deaths of 80,000-100,000 Poles and 10,000-15,000 Ukrainians. According to Timothy D. Snyder, the term is still used (often pejoratively) to describe Ukrainian nationalists who sympathize with the fascist ideology and consider themselves followers of the OUN-UPA myth in modern Ukraine.

This video is from the 1st of March 2014

“Man learns from history that man learns nothing from history.”

~Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel